Bleeding Kansas: The True Beginning of the American Civil War (Part 1)

When I first began studying the American Civil War, I—like a lot of armchair scholars—focused on events in the East. Oh, I had read about Pea Ridge, Shiloh, Corinth, and Chickamauga. But the East was where I thought the most important action had taken place.

That would change on a trip from Missouri to Savannah, Georgia. My ex-wife and I were on I-75 when I saw a road sign for the Allatoona Battlefield. I had seen it before, but something pushed me to stop this time.

We took the exit and soon found ourselves at the head of the trail to the earthworks. There, just off the parking lot, I saw a very large monument carved into the shape of Missouri commemorating the men of the Missouri Confederate Brigade. I was perplexed. Who were these men? Where did the all come from? And what made them fight and die so far from home?

Thus began a study of the Missouri Brigade and the war in the West. My endeavors ultimately led to me writing a novel, Covenants of the Heart, due to be published in June of 2015, which follows the Brigade’s history.

My perspective on the War was turned on its head: I came to the conclusion that the war was actually won in the West. More importantly—and contrary to what I had been taught in school—the Civil War actually began in the West. It didn’t start in April of 1861 in Charleston Harbor. It actually began in 1854 on the Kansas prairies.

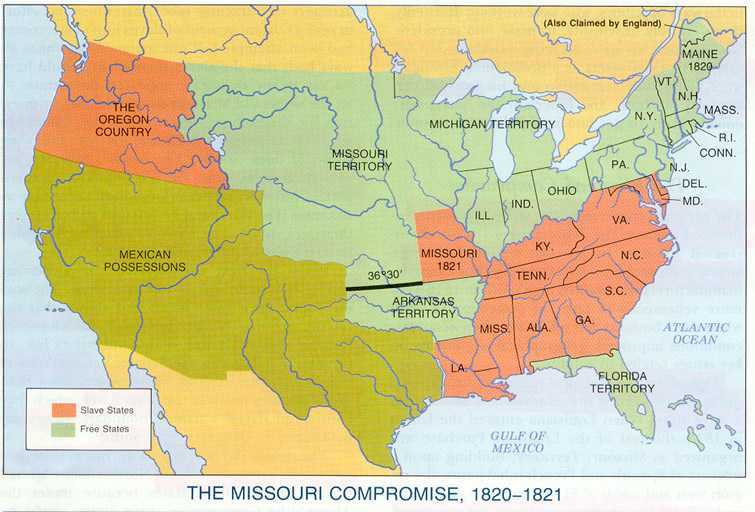

While the issues over slavery and State’s Rights go back to the founding, in my estimation the events that led to the war began with the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. It was the last in several attempts to affect a compromise between slaveholding interests and abolitionists. Its author was Stephen Douglas, the Democrat Senator from Illinois. Prior to its enactment, the expansion of slavery was effectively restricted by the Missouri Compromise of 1820. That Act prohibited slavery in the Louisiana Purchase north of the 36°30’ parallel except for what would become the State of Missouri. This meant that slavery was allowed in Arkansas Territory which included what is now northeast Oklahoma. It was outlawed north of the Territory’s northern border, again except Missouri. This effectively meant that pioneers from southern states would be barred from the vast majority of the Louisiana Purchase.

In the time between the passing of the Missouri Compromise and The Kansas-Nebraska Act, the United States acquired the land west and southwest of the Louisiana Purchase. While the Compromise probably delayed the outbreak of open hostilities, it didn’t get rid of the ongoing debate over slavery and competition for power between proslavery and abolitionist forces. The Kansas-Nebraska Act was designed to end the debate by basically saying:

- Stop ‘discriminating’ against slaveholding pioneers and open up all territories to the possibility of slavery. (In technical reality, they were already open to all. It’s just that southerners would have to leave their slaves behind, something many—if not most—wouldn’t even consider).

- Let the question of permitting or prohibiting slavery be decided by popular election of territorial residents.

What seemed to be quite rational and pro-democracy on the surface didn’t take into account the passions on both sides. The new Kansas Territory soon found itself to be the target destination of abolitionist settlers from the northeast and the Midwest, many who actually formed corporations, societies, and other organized groups who—in addition to looking for new homes—were determined to keep Kansas free. Similarly, proslavery groups also crossed the border with the notion to extend the “peculiar institution” to the Territory.

Thus the seeds for violence were planted which would sprout in late 1854, grow in 1855, and burst into full bloom beginning with the Sack of Lawrence on May 21, 1856. Lawrence was the main outpost of abolitionists. When push came to shove, after competing state governments had been elected and a few deaths occurred, the town was invaded by some proslavery Kansans backed up by Missouri militia units. After some bickering back and forth, ex-senator David Rice Atchison allegedly aimed a cannon at the Free State Hotel. He fired and missed the whole building. Thereafter, the town was looted and the hotel burned.

But that wasn’t the end of “Bleeding Kansas.” The Pottawatomie Massacre saw the deaths of five proslavery men on May 23, 1856. The “Battle” of Black Jack took place on June 2, 1856. Other fights between free-state and proslavery men occurred on August 11th, August 15th, and August 16th, and August 25th.

And so it went—years before P.G.T. Beauregard and Edmund Ruffin fired that fateful shot in April of 1861. In fact, I think the Sacking of Lawrence is much more emblematic of what happened in the war. The South had a great shot at independence, but its leadership misfired.